Table of Contents

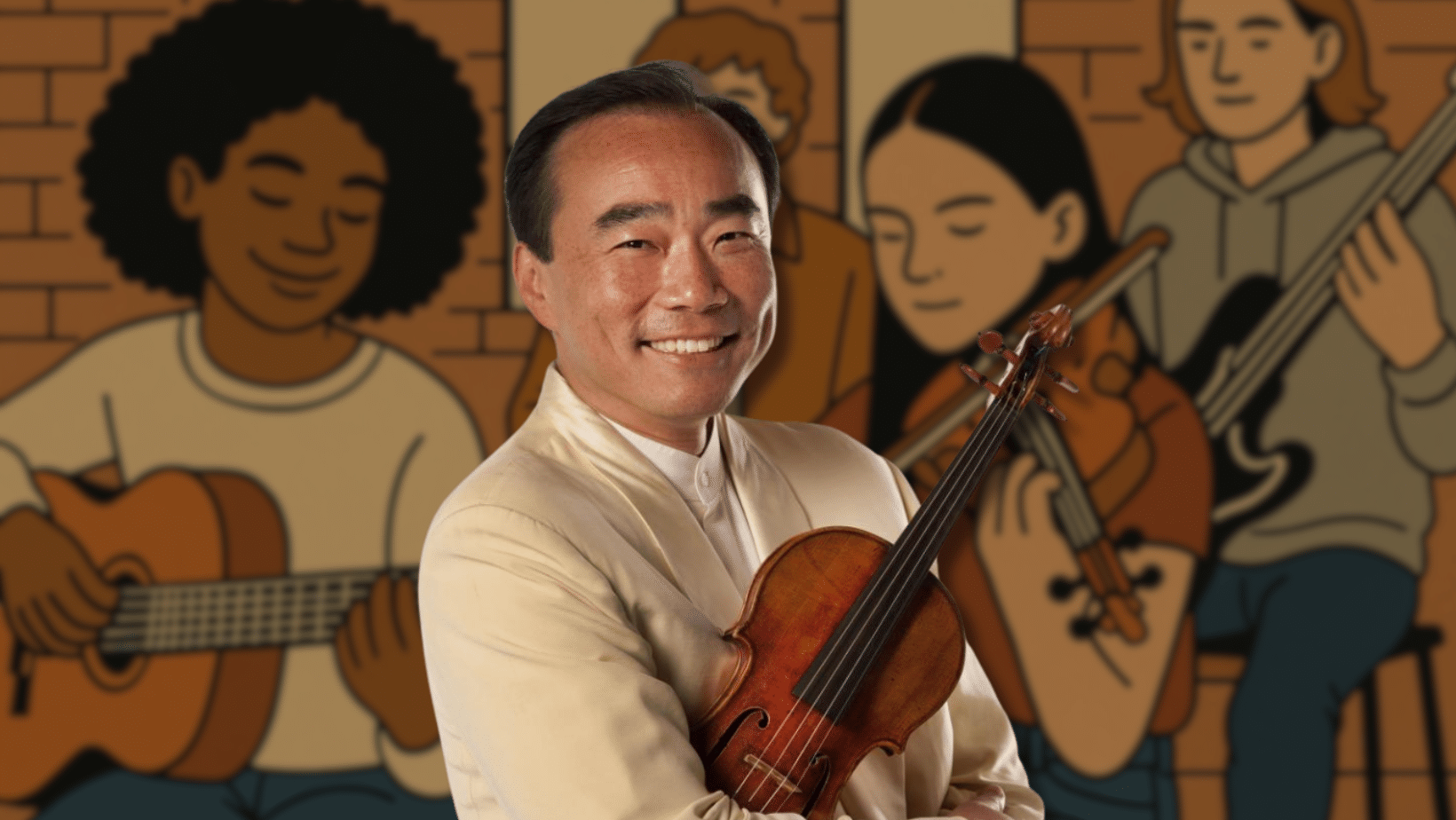

Over 70 percent of professional musicians suffer from anxiety and depression, triple the general population’s rate. For those labeled “child prodigies,” the numbers worsen. Houston, Texas-based violinist Cho-Liang Lin, who has performed with leading orchestras for six decades after starting as a young talent himself, reveals how the industry’s obsession with prodigies creates a destructive trap. His insights from teaching at Juilliard and Rice University expose how methods meant to create musical genius often destroy the humans behind the instruments.

From Talent to Commodity

Cho-Liang Lin witnessed classical music’s transformation during his journey from Taiwan to premier concert halls worldwide. Starting violin at five, moving alone to Australia at 12, then New York at 15 for Juilliard, Lin was performing 100 concerts annually by age 21. Yet he rejects the prodigy label.

“I never regarded myself as a child prodigy, never,” Lin stated recently. “I read plenty of biographies about great child prodigies, especially among violinists, and I thought they were just outright geniuses, that stuff of legends that I could never match.”

His early years reveal intense pressure young musicians face. After his father died when Lin was 11, the family navigated Taiwan’s martial law restrictions to obtain exit permits for his musical education. The government required him to pass a “Young Genius Award” examination, which Lin calls “a total misnomer,” exemplifying how institutions commodify young talent.

Lin pinpoints a crucial industry shift in the 1980s. “Being brilliant at age 14 did not mean a whole lot in the late seventies, early eighties. Then somehow in the middle eighties, that became really fashionable.” Even today, as Cho-Liang Lin’s professional career continues with performances worldwide, Lin observes how this commodification persists.

One of Lin’s students experienced this commodification firsthand. After earning major soloist engagements as a young violinist, management dropped her when she outgrew the “cute little child prodigy” phase.

“She was totally lost as to what she wanted to do,” Lin recalled. “I hated her handlers for that. But there’s nothing you could do because it’s done. It’s a business decision. It’s very crude, but it’s unfortunate and true.”

Research confirms these patterns. A 2016 study by Sally Gross and George Musgrave found 68 percent of professional musicians experience depression and 71 percent suffer anxiety, rates far exceeding the general population’s 22.5 percent.

When Practice Becomes Prison

Young musicians face another trap in obsessive practice culture. Lin’s perspective surprises those expecting him to advocate extreme dedication.

“When I was their age, there was nothing to distract me. There was no phone, no cell phone, not even email or not even fax. Once I walk into a practice room, I do nothing except practice,” Lin explained. Yet he immediately adds, “If you do quality practicing for one hour, that’s better than two hours of wandering around.”

This distinction matters profoundly. Lin watches students waste hours in practice rooms while texting, practicing five minutes, then returning to phones. “That’s pretty useless,” he states. Quality practice requires focused attention on specific problems, not mindless repetition.

Research validates Lin’s observation. Music students seek psychotherapeutic help far more frequently than other students, with isolation and excessive practice hours identified as primary factors. A Frontiers in Psychology study found perfectionism combined with social isolation creates mental health crises.

Lin describes a saxophonist student whose dedication became pathological. “On weekends he would wake up early and practice until it was time to sleep, often 15 hours a day. He became very uneasy when he wasn’t practicing. He didn’t want to do anything fun, like spend time with his friends.”

The family encouraged breaks. While this briefly helped, the student eventually burned out completely, later blaming his family for disrupting practice. This demonstrates how young musicians lose perspective, internalizing myths that only extreme sacrifice brings success.

Redefining Musical Success

Lin challenges conservatory culture’s narrow success definitions through philosophy and action. Traditional training prepares students for two careers: orchestra member or soloist. Yet major orchestras might have one opening yearly per instrument, attracting hundreds of global applicants.

When a talented student dreamed of joining the Boston Symphony, Lin presented this reality, then offered alternatives. He suggested pursuing an MBA for arts administration or board positions.

“You can help them choose policy courses as well as the next music director. Also, hugely important,” Lin told her.

Meeting her later at a Houston supermarket, she admitted working at a bank and no longer playing professionally. Lin’s response was revolutionary: “Good for you. I don’t mind that you quit the violin. You could always pick the violin up and play in an amateur orchestra. That’s a lot of fun.”

Within a year, she was driving a Porsche. Another performance-anxious student entered medical school. Lin celebrates both outcomes from his Houston base, where he’s taught at Rice University’s Shepherd School of Music since 2006, acknowledging what conservatories rarely admit: most graduates won’t have traditional performing careers, and that’s perfectly fine.

“Regardless what your career path is, I hope you learn how to work with other people,” he tells students. “You are in an orchestra and you have to play well in order to support others, but you’re not always the star.”

Lin recognizes musical training develops critical life skills: discipline, collaboration, creative problem-solving, and emotional expression. These abilities serve graduates whether performing at Carnegie Hall or developing software. This philosophy extends to his own diverse career, which includes festival appearances and educational initiatives alongside traditional performances.

Building Healthier Futures

Lin’s experience with a New York amateur orchestra crystallized crucial lessons. Initially dismissive, he discovered the ensemble consisted of Juilliard graduates now at Google and Facebook.

“They actually all attended top music schools except after graduating, they all opted to do something else,” Lin marveled. “They love their music, miss it. They miss playing their instruments. So they get together three times a year.”

Their exceptional playing and pure joy, freed from professional pressure, revealed something profound. These musicians achieved what many professionals lose: genuine love for the art form.

Music education must broaden success definitions beyond performance. Former musicians excel in medicine, technology, finance, and law because they understand discipline, precision, and long-term goals. The Grammy-nominated artist emphasizes that musical excellence comes in many forms beyond traditional concert careers.

Organizations like Amber Health, addressing musicians’ mental health since 2020, mark progress. The Mental Health in Music survey documenting 70 percent of independent musicians struggling with anxiety and depression brought overdue attention.

Parents and teachers must resist creating “prodigies” through excessive pressure. Lin’s parents offer a healthier model. “They wanted me to study the violin so that I could appreciate culture, that I would become a well-rounded person.” They never intended professional music. This approach may have enabled Lin’s success by preventing identity crises that derail many pushed toward musical careers from infancy.

Breaking the Trap

Cho-Liang Lin succeeded by rejecting prodigy mythology while maintaining perspective on music’s place within life. His story offers a reform blueprint, though implementation requires confronting entrenched beliefs. Even as he continues performing internationally, Lin remains committed to reforming music education.

“Technology democratizes education, but it’s still crucial to maintain the personal connection that music thrives on,” Lin notes. He sees potential in digital tools but warns against losing music’s human elements: mentorship, collaboration, and emotional communication.

Lin’s message confronts an industry trading on precocious youth spectacle while discarding those who age beyond marketability. Genuine musical excellence doesn’t require sacrificing mental health or human development. It demands abandoning mythology that traps young musicians in anxiety, depression, and burnout cycles.

Some conservatories have begun incorporating wellness programs and career diversity training, but systemic change requires deeper shifts in defining musical success.

Music education faces a clear choice. Continue producing damaged prodigies and burned-out professionals, or embrace Lin’s vision of training that develops complete human beings. For future musicians’ sake, the answer should be obvious. The question remains whether an industry built on exploitation of youthful talent can transform itself before destroying another generation of promising artists.

Feature Image: Cho-Liang Lin Child Prodigy.png